The following article was written as an assignment for the Journalism and Society class.

|

| Metropolitan Coalition Against Nukes (MCAN) |

As more people become constantly connected online through computers and mobile devices in the last few years, more social demonstrations and protests have been organized and done all over the world with the help of the Internet. The situation is the same in Japan. There have been many social demonstrations and protests organized with the help of various social networking services such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube,

Nico Nico Douga (a Japanese video-sharing site), IRC (Internet Relay Chat), and

2channel (the Japan's biggest bulletin board site). Japanese web-driven activism has its unique characteristics. Participants tend to hide their real identities and keep anonymous while participating in protests and activities. Japanese tendency to be anonymous online is often pointed out in earlier study

(Bovee and Cvitkovic, and

McLelland), but has not examined yet in detail with the recent demonstrations and the uses of social networking services. In this paper, I would like to examine how the recent web-driven social activism has been operated on different web platforms and services in Japan, and finally show how anonymity plays an important role in the Japanese demonstrations and protests.

|

| Metropolitan Coalition Against Nukes (MCAN) |

There were roughly four notable web-driven social protests and activities occurred in 2012 in Japan. One of them that drew most media attention was the anti-nuclear demonstration held in front of the Prime Minister's Office in Tokyo. It was organized by a group called

Metropolitan Coalition Against Nukes (

MCAN). It started in March 2012 and continued weekly since then. The number of participants has, however, decreased from 21,000 at a maximum to several hundreds today (estimated by police. "

Anti-nuke Protests"). At their peak, they even had an official 30-minute interview with the then Prime Minister Noda in the Office (

Nakanishi). There are several characteristics that are particular to MCAN. One of them is that they are a single-issue group. Their only purpose is to stop all the nuclear power plants in Japan. The group leader banned the participants to claim other political issues during the protests. The other interesting point is that they mainly use Twitter and Facebook for announcements ("

First Anniversary"). It was these social networking services that increased the number of participants from 300 at first to "200,000" at its peak (according to MCAN. "

Anti-nuke Protests"). Another point is that only a very small number of individuals have identified themselves in the group. On the top of their website, there is a list of anti-nuclear groups that join MCAN. It makes sense since they call themselves "a network, not a group," but there is no individual name on the list other than the name "voluntary individuals" ("

Sanka Gurupu" All translation mine) added at the end. Regarding the protesters, the organizer does not know who they are since the MCAN's messages are retweeted again and again on Twitter. People usually participate in the protests without telling their true identities (some even wear masks to cover their faces). Even the representative of the group,

Misao Redwolf, does not reveal her real name. Still, many participants show their faces and protest even in front of TV crews. Overall, the organizer and participants seem to conceal their individual identities, whereas the demonstration itself is quite visible from the outside.

|

| Zainichi Tokken o Yurusanai Shimin no Kai (Zaitokukai) |

The other notable demonstration that drew the media attention recently is anti-Korean protests that have been done since 2012 at Shinokubo in Tokyo. It was organized by an ultranationalist group called

Zainichi Tokken o Yurusanai Shimin no Kai (Citizen Group That Will Not Forgive Special Privileges for Koreans in Japan), also known as

Zaitokukai. Their hate speeches such as "Kill Koreans!" and "Get rid of the cockroaches from Japan!" were so aggressive and racist that they often had conflicts with the local Korean residents ("

Arita Appeals"). They have also made racist insults against other foreigners including Chinese and the Westerners. They started their activities in 2007 and now have 9,000 members. They have local branches all over Japan and routinely hold small-scale demonstrations (

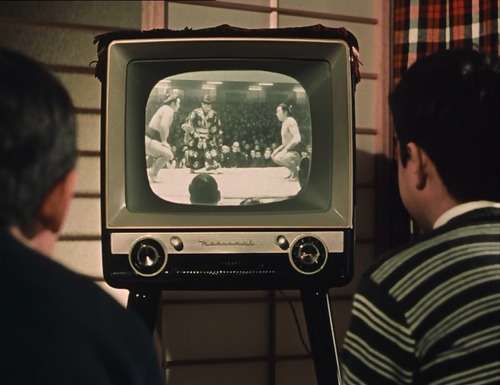

Fackler). One of the interesting points of this group's activities is that they use videos to show their performances on YouTube and Nico Nico Douga and appeal to their viewers effectively on the web. They shoot several videos on each demonstration they do and upload them on these sites regularly so that they can get more supporters through these sites. They are said to be strongly supported by

netouyo, the Net far-right group known as anti-Korean and Chinese. Their demonstration videos are popular enough to go to the upper part of the video chart in the politics category on Nico Nico Douga, which is the Japan's largest video-sharing site with more than 30 million registered users. Since the site has its own unique streaming comments function in which the other users' comments go from right to left on the screen while watching. The viewer feels as if he or she is watching a live video together with the other viewers. The comments are short and quick to fade out, and most of them are shouts and agitations. Unlike those on YouTube, it is rare to find calm and rational comments that can be developed into a productive discussion. Instead, watching the aggressive attacks of the protesters in the video with hundreds of hateful comments overlapped on it is so visually impressive that the viewer feels as if he or she were in the same heat with the protesters and other viewers. This pseudo live-experience on Nico Nico Douga is the key driving force for Zaitokukai to gain today's popularity on the web.

|

| Makoto Sakurai |

The other interesting point of Zaitokukai's activities is that like MCAN, the members do not identify themselves in public. Even the founder and representative of the group

Makoto Sakurai (which is not his real name) does not reveal his own identity. At their demonstrations, many participants wear sunglasses and masks during the march in order not to identify themselves. They are also a single-issue group like MCAN and do not have a concrete ideology such as the Nazi's racial supremacy theory. They are loosely connected through the Internet and get together only for the demonstrations (

Fackler). The web supporters who watch the group's videos on Nico Nico Douga are even more anonymous. They do not reveal their names either since a viewer cannot trace the comments back to the original posters. Even if he or she can, almost no user uses his or her real name on Nico Nico Douga and does not use his or her face-photo icon, either. Overall, it can be said that the protesters are present in the real world just like the MCAN participants, but hide their true identities more than the anti-nuke protesters do. The supporters are more invisible than those of MCAN since Facebook and Twitter that the MCAN supporters often use for spreading information are more identity-oriented and less anonymous than Nico Nico Douga.

.png/250px-Topimage_(2ch).png) |

| 2channel |

Inarguably, the most notorious and aggressive web-based activism in Japan today is Kijo group that bases on particular threads on 2channel. 2channel (also known as 2chan) is "the biggest BBS in the world" (

Katayama) with 2-3 million comments posted a day on more than 800 active boards (

Suzume graph). The estimated number of the active users of the site is between 12 and 16 million (

Matsutani). There are a variety of boards on any kind of topic that one can think of, even on harmful and illegal topics such as murders, weapons, drugs, and poison. Due to the size of the site, some boards are chaotic and become a lawless area so that the threads are filled with illegal drug deals, prostitution ads, gun sales, and even death threats. However, the distinctive feature of this site is that all the messages can be posted totally anonymously without any registration. Although the IP address can be detected and shown to the police by request in the worst cases such as a death threat (open proxies are banned from posting on 2channel), all the comments are posted under the name of "anonymous." On the other hand, since the posters can hide their real identities, they tend to confess their true feelings more and often leak their company's secret information on the boards. In essence, 2channel works as the outlet of complaints and angers accumulated in the society. This is especially true in Japan where people have to say

tatemae (public statement) and

honne (personal feeling) separately in their daily communication with others. Although the boards are full of slander, hate speeches, and defamation and 99.9% of the comments are useless, "an excellent source of information" (

Matsutani) can be found here. That is why news organizations follow 2channel closely to find news sources and see the public mood (

Onishi and

CNN).

|

| Kijo threads on 2channel |

Among the huge numbers of the threads on 2channel, the Kijo threads are known as the most fearful and aggressive ones. Kijo is an abbreviation for

kikon josei, which means married women in Japanese. The threads were originally made for married women to chat about their daily topics. The direction on the top of the threads clearly says that the threads are only for married women and others cannot post any comments there. What actually happens on these threads is that the posters intensively dig up the personal information of an ordinary person or celebrity in the latest news and reveal it on the threads. They have such excellent searching skills both on the web and in the real world that they disclose any kinds of personal information including the person's photo, address, school/company's name, phone number, and email address. They reveal the person's family information as well. They sometimes go to the related locations and upload photos. At the same time, they encourage other viewers to make phone calls and send emails to the person's school or company as well as asking to report the event to police and authorities. They continue to reveal the information until the person shuts down his or her blog, and deletes his or her Facebook, Twitter, and email accounts. In the worst case, the targeted person often has to change his or her school and workplace because of these attacks. For example, several jr.-high school students, who bullied their classmate to death in Shiga prefecture in 2011, were set as targets by the Kijo group since media did not report their names (because they were minors) and the school committee did not investigate the case at first. In this case, all the personal information of the students, their family members, and the class teacher were disclosed on the threads. Most of them finally had to move and change their schools ("

Student Suicide"). This is typically how the person on a target is crucified on the Kijo threads.

|

| Kijo threads' icon |

The Kijo group is different from the MCAN and Zaitokukai cases in the point that they do not show themselves in the real world or on the web at all. Their real identities are hard to trace. It is doubtful that they are actually married women even though their comments sound very feminine. According to a survey done by an Internet survey company, the estimated active users on the Kijo threads who spend more than two hours per month are about 16,000, but married women account only for 36% of the total. Single women account for 16% and the rest are probably men in their 30s and 40s (

Yamamoto). Since their postings cannot be identified with particular individuals, there is little community feeling (

McLelland 822). In a word, they emerge as a collective unconsciousness on the web that searches for a target to hang up.

|

| Anonymous |

Among all the recent big web-driven activism in the world, the most famous one is definitely the protests done by a hacker group called

Anonymous. They usually use IRC to discuss issues and communicate with others. They have a strong link to Japan. Christopher Poole adopted the 2channel system and made the same anonymous BBS called 4chan in 2003, on which the Anonymous was originally formed. They had also attacked and crashed authorities' and companies' servers in Japan in June 2012 due to the protest against the new laws that ban illegal downloading. While this was done by the

AnonOps (the mainstream of Anonymous), the

OpJapan (a Japanese branch of the group) took a different approach to the issue. They did

a cleanup activity in Tokyo wearing a suit and Guy Fawkes' mask without saying anything or holding placards. On July 7th, 2012, about 50 Anonymous members gathered, picked up garbage, and handed out leaflets that explain why they were doing so to the passerby ("

Dos and Don'ts").

|

| Anonymous Cleaning Service in Shibuya |

Although they call the activity "off-meeting, not a protest" ("

Dos and Don'ts"), this protest style is very different from those of the other groups mentioned above. First of all, they identified themselves as the members of Anonymous and showed themselves in the real world with Anonymous characteristics. Unlike the MCAN and Zaitokukai demonstrators, they strongly presented themselves as a character so that they can keep their clear online identity while hiding their individual ones. On their website, they listed detailed directions and rules for the participants such as "Act politely" and "Don't do any activities that go against the laws" (

"Dos and Don'ts." Translation mine). The event was vastly reported on more than 20 news outlets in Japan and the world. It was a well- defined, successful media representation of the group while keeping their true identities anonymous.

|

| Hierarchical conditions of anonymity |

The four protest styles mentioned above have different degrees of anonymity in their activities, but in all the cases, the participants' real names are not shown. These degrees of online anonymity can be roughly classified into three phases (

Bovee and Cvitkovic 42-43). The lowest degree of anonymity can be called

visual anonymity, at which the person usually retains some connection to the real self in the society (e.g. email address). The second level is

the dissociation of identity, in which the person adopts a new online identity (such as a handle name or graphical avatar). The highest level of anonymity is

the total lack of identification. On this level, the person lacks an avatar or any label that would mark him or her as an individual. According to these anonymity classifications, the MCAN protesters can be categorized as the visual anonymity since many of them use Facebook that links the person to his or her real identity. They also show themselves on the street without any disguises. The demonstrators of Zaitokukai can also be categorized in this level since some of them show their faces in the video, but their online supporters who watch their videos and post comments on Nico Nico Douga are on the lack-of-identification level since only their comments are left without any avatars or nicknames (a comment poster's nickname and avatar are traceable on YouTube). The Kijo group on 2channel is surely categorized as the lack-of-identification level since there is nothing but their comments and it is almost impossible to identify them. On the other hand, the OpJapan group of Anonymous is categorized as dissociation of identity since they all have the unique character of Anonymous.

|

| Metropolitan Coalition Against Nukes (MCAN) |

How do the different degrees of online anonymity affect the formation of the group then? According to

the Social Identity Model of Deindividuation Effects (

SIDE model) on computer-mediated communication (CMC), "the combination of anonymity and group immersion ... or interaction via computer network ... can actually reinforce group salience and conformity to group norms" and "perceive the self and others not as individuals with a range of idiosyncratic characteristics and ways of behaving, but as representatives of social groups or wider social categories" (

Postmes T, Spears R, and Lea M 697). Based on this SIDE model, it is very clear that anonymity highly worked for MCAN and Zaitokukai to form and develop their groups to the sizes of today. It can also be inferred that all the four groups strongly believe in their doing something good for ‘social justice.' Another CMC study shows that online anonymity fosters deindividuation and a more impersonal, task-oriented focus (

Walter 361). This is also backed by the MCAN strategy that more people could participate in the protests because the events were single-issue rather than multi-issue. The MCAN staff had deliberately removed the protesters who claimed other social and political issues in the demonstrations and declined to change their single issue to wider social problems. They keep themselves away from old left-wing social activist groups, too (

Nakanishi). Zaitokukai also does not bring Japanese traditional Shintoism or militarism into their policy like old right-wing groups and represent themselves just as xenophobia (some participants hold Japanese imperial flags during the protests). The Kijo group on 2channel intensively search and attack the target as long as the personal information is there. They immediately vanish when the target is knocked off and there is no more information to dig up. All the examples show that unlike the old social and political activists and protesters in the 60s and 70s, today's Japanese protesters seem to temporarily gather on a single issue and avoid one's activities being seen as a part of one's character or personality by the others in their real lives.

|

| LDP leader Shinzo Abe |

The point that single-issue protests do not seem to last long or gain popularity in Japan can be examined from another point of view. The fact that the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP) won a substantial victory on the Lower House elections in December 2012 shows that even the MCAN, which once had more than 20,000 people in the protest, could not have enough influential power on the public to bring its issue to politics because the LDP is the only party that did not insist on anti-nuclear policy during the election campaign (all the other parties that claimed anti-nuclear drastically lost their seats). Zaitokukai, Kijo group, and Anonymous still cannot gain broad support from the public in Japan and are just seen as evil in the digital era. These cases suggest that their online anonymity kept them from gaining popularity and credibility from the public and developing into the mainstream in Japan.

Overall, the examples of the recent web-driven activism in Japan mentioned above obviously show that "Japanese seem to prefer greater anonymity online" (

Bovee and Cvitkovic 50), but it can also be said that unlike the other big web-driven social movements such as Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street in the world, these activities in Japan would have never occurred through Facebook. This is probably because the site does not allow anonymity and fake identities at all for its users. The huge expansion of 2channel clearly shows that Japanese need a virtual space to let out all the frustrations anonymously that pile up in their stuffed

tatemae/

honne society.

.png/250px-Topimage_(2ch).png)

.jpg/249px-My_Neighbor_Totoro_-_Tonari_no_Totoro_(Movie_Poster).jpg)

The plot of Antigone can be described as a chain reaction of tragedies. Creon, who has just taken the power of the Thebes, orders to ban the burial of Polyneices who betrayed the state. This is Creon's first trial to show his power to the people he governs. However, Antigone defies his order and holds a funeral for his brother. Creon orders to send her to the prison. There she hangs herself. Following her death, her fiancée and Creon's son Haemon kills himself, too. Out of despair, Haemon's mother and Creon's wife Eurydice also kills herself. Creon is terribly shocked at realizing that his orders have ended up in this way. Besides these characters, Antigone's sister Ismene, the prophet Teiresias, and the Chorus, which represents the citizen's voice in Thebes, sometimes encourage, sometimes discourage the characters' intentions, and influence their decisions throughout the drama.

The plot of Antigone can be described as a chain reaction of tragedies. Creon, who has just taken the power of the Thebes, orders to ban the burial of Polyneices who betrayed the state. This is Creon's first trial to show his power to the people he governs. However, Antigone defies his order and holds a funeral for his brother. Creon orders to send her to the prison. There she hangs herself. Following her death, her fiancée and Creon's son Haemon kills himself, too. Out of despair, Haemon's mother and Creon's wife Eurydice also kills herself. Creon is terribly shocked at realizing that his orders have ended up in this way. Besides these characters, Antigone's sister Ismene, the prophet Teiresias, and the Chorus, which represents the citizen's voice in Thebes, sometimes encourage, sometimes discourage the characters' intentions, and influence their decisions throughout the drama.