MA research proposal

This is my current proposal for research I’m doing as part of the Master of Learning Sciences and Technology. I’ve been quite fascinated by Personal Learning Networks (PLNs) for a while now, and as a learning practitioner, I’m interested in how we leverage our PLN relationships to support improvements or innovations in our professional practice. This is what my proposed research aims to explore. This proposal will be refined, and possibly change in some parts…so it’s always good to be able to look back and see how it evolves.

Introduction

Increasing competition, globalisation, and rapid pace of change are putting organisations and individuals under pressure to continuously innovate (improve processes, products, practices) (Whelan, 2007, Baker-Doyle 2008). Knowledge is often recognised as an organisation’s greatest asset (Whelan, 2007); and in this “knowledge economy” the ability to communicate and collaborate effectively across contexts is vital to survive and thrive (Castells, 2000, cited by Baker-Doyle, 2008). Quantitative research using Social Network Analysis (SNA) has shown that knowledge flows for organisational innovation happen through informal social networks both within and outside the organisation (Cross et al, 2002; Phelps, Heidl, & Wadhwa, 2012; Swan & Scarbrough, 2005; Bessant, 2012; Whelan, Parise, de Valk, & Aalbers, 2011; de Laat & Schreurs, 2013; Van Den Hooff, Van Weenen, Soekijad, & Huysman, 2010; Tagliaventi & Mattarelli, 2006; Hemphala & Magnusson, 2012; Mackey & Evans, 2011).

Whilst this research has defined some of the structural characteristics of networks that support innovative practice (e.g. Burt 2004, Ebadi & Utterback 1984, Morrison 2002; Perry-Smith 2006; Morgan & Soerensen 1999 – cited byPhelps et al, 2012; Fleming, Mingo & Chen 2007; Obtsfeld 2005), less is known about the processes that link these networks to innovation (Swan & Scarbrough 2005; Phelps et al 2012), what people actually do within networks, how they maintain relationships (deLaat & Schreurs 2013), and the social rules and practices they use to negotiate meaning (Ryberg & Larsen, 2008).

Using qualitative case study research, this project aims to provide a rich description of how personal learning networks may support workplace learning and improvements in professional practice for Learning & Development (L&D) professionals working in an organisational context. In the modern, knowledge-based organisation, L&D professionals will be expected to help build employees’ “network performance” capabilities (Martin & Handcock, 2014). To do this, L&D professionals first need to understand how to build these skills themselves, to improve their own professional practice. This research will help them do this.

Literature review

Innovation is “typically understood as the successful introduction of something new and useful” (Dasgupta & Gupta, 2009). Radical innovation results in extreme change to existing processes, practices, products while Incremental innovation leads to gradual, or step by step improvement (Dasgupta & Gupta, 2009). In an organisational context, this may be understood as daily learning and emergent adaptation of work practices, through informal, spontaneous information gathering, iterative experimentation, and observation (Brown & Duguid, 1991). It is a “type of conduct” embedded in the social networks of individuals (Obtsfeld, 2005).

Literature on learning and knowledge networks consistently draws links between networks and innovation, innovative practice, or improvements in professional practice (e.g. Phelps, Heidl, & Wadhwa, 2012; Swan & Scarbrough, 2005; Bessant, 2012; Whelan, Parise, de Valk, & Aalbers, 2011; de Laat & Schreurs, 2013; Van Den Hooff, Van Weenen, Soekijad, & Huysman, 2010; Tagliaventi & Mattarelli, 2006; Hemphala & Magnusson, 2012; Mackey & Evans, 2011). Social networks research has shown that an extended network is crucial for personal and professional development (Haythornwaite & de Laat, 2013), including the implementation of innovations and improved practices (Baker-Doyle, 2008; Haythornwaite & de Laat, 2013). Informal, interpersonal relationships that employees build with others both inside and outside the organisations are key (Whelan et al 2011; Tagliaventi and Mattarelli, 2006). Weak ties, with acquaintances (often outside the organisation) help bring in new ideas that inspire and challenge existing practice; strong ties with people within the organisation who you are close to, and have a shared practice with, help individuals to interpret, adapt and implement new ideas into the local context (Haythornwaite & de Laat, 2013; Kijkuit and Van den Ende 2007; Hemphala & Magnusson 2012). In particular, co-location / shared physical space, combined with common values seem to be critical for supporting exchange of knowledge about new practices, and adoption and diffusion of new practices amongst practitioners (Tagliaventi and Mattarelli, 2006; Baker-Doyle, 2008; Hotho, Becker-Ritterspach, and Saka-Helmhout 2013).

The development of shared professional practice amongst practitioners is grounded in socio-cultural theories such as situated learning theory, which views engagement in activities and with others as participation in social practices (Greeno & Gresalfi, 2008; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Packer & Goicoechea, 2000; Wenger, 1998 – cited by Bonderup Dohn, 2014). Engagement is intrinsically related to belonging; and participation is a negotiation of one’s status and identity within the community (Bonderup Dohn, 2014). Learning and knowledge cannot be separated from the context in which it occurs, and is usually embedded in social interactions with others (Bell, Maeng, and Binns, 2013).

One particular type of informal relationship is a Personal Learning Network (PLN). A PLN is “the network of people a self directed Learner connects with for the specific purpose of supporting their learning needs” (Rajagopal, Verjans, Sloep & Costa, 2012). An individual’s PLN may contain a broad range of connections, including weak and strong ties, within and outside the boundary of their professional practice. Whilst there has been relatively little academic research on PLNs, there is increasing anecdotal interest in PLNs amongst learning and education practitioners documented in blog postings or conference presentations (Couros, 2010), and industry publications – e.g. a search on the Association for Talent Development’s ‘TD’ magazine http://www.astd.org/Publications/Magazines/TD yielded 495 results.

Studies suggest that practitioners are motivated to develop PLNs to support innovations in their professional practice, by including ‘innovative’ people in their PLN (Rajagopal et al 2012).Practitioners connect with these people to draw on their knowledge and experience in order to improve their own professional practice, or to get support from others facing similar workplace challenges (Lalonde, 2011).

Effective use of PLNs as learning resources depends on the networking skills of individuals – – the ability to engage in conversations, communicate ideas and opinions, and to continuously build, maintain and activate relationships (Rajagopal et al 2012). PLN relationships are often developed and sustained via Information and communication or social networking technologies (Rajagopal et al 2012, Lalonde 2010).Whelan et al (2011) found that employees who brought innovative ideas into their organisation via their external networks (“idea scouts”) had a high level of comfort and skill in navigating and utilising web 2.0 technologies (social bookmarking/tagging, social media platforms, blogs, wikis), were about 3 times more likely to learn of new developments and trends this way compared to face-to-face channels.

Much of the research on networks and innovation describe what networks offer in general terms (deLaat & Schreuers 2013), assume networks play a positive role (Swan & Scarbrough, 2005), and don’t always represent the complexity of the relationships and ties between people (Ryberg & Larsen, 2008). More longitudinal, process-oriented, case-based qualitative research (Phelps et al, 2012), ethnographic studies, and/or grounded empirical approaches (de Laat & Schreurs, 2013), describing networked learning behaviour is needed, the processes linking networks to innovative practice (Swan & Scarbrough 2005; Phelps et al 2012), what people actually do within networks, how they maintain relationships (deLaat & Schreurs 2013), and the social rules and practices they use to negotiate meaning (Ryberg & Larsen, 2008).

Methodology

Research strategy

Although there are many anecdotal and industry articles stating the benefits of developing and sustaining a Personal Learning Network (PLN) for learning professionals to improve and support their professional practice, there is an absence of academic research for this target population. This study seeks to explore and describe how relationships in a learning professional’s PLN might support them in their professional practice. The primary research question is:

In what ways do relationships in a learning professional’s Personal Learning Network support them to introduce improvements or innovations in their professional practice?

Secondary research questions include:

- How do strong/weak connections external to the learning professional’s organisation support this?

- How do strong/weak connections internal to the learning professional’s organisation support this?

- What role does the learning professionals’ skill, experience and comfort with social media technologies play in facilitating this?

A retrospective case study research strategy will be employed to enable an in-depth exploration, helping to contribute to theory (Neuman, 2003), of “how and why” (Fridlund, 1997) a learning professional’s PLN might contribute to improvements in their professional practice.

Operationalisation of key concepts

The learning professional’s “Personal Learning Network” will be operationalised as people they interact with for the purposes relating to work or their professional practice.

“Improvements in professional practice” will be operationalised using the dimensions of “absorptive capacity” used by Hotho et al (2012) in their comparative case study of two subsidiaries. “Absorptive capacity” is defined as “the ability and motivation to recognise, assimilate and apply new knowledge” (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Minbaeva et al., 2003 – cited by Hotho et al 2012), and is frequently highlighted as a key determinate of knowledge transfer, innovativeness and profitability of organisations (Hotho et al, 2012). Adapting Hotho et al’s (2012) operationalisations, this study will look for evidence of:

- Acquisition of ideas or information relating to professional practice from members of their Personal Learning Network

- Transformation in thinking about their professional practice resulting from an interaction with their Personal Learning Network

- Application of this knowledge through the adoption of new practices or changes to existing practice.

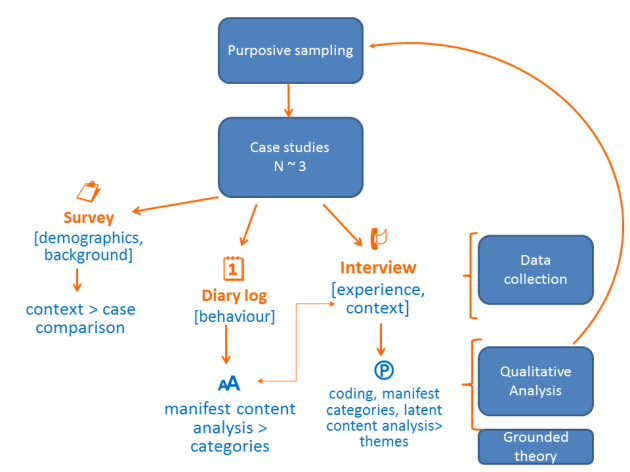

Figure 1. depicts the design for the case studies. Sampling, data collection, ethics and analysis will be described in more detail in the following sections.

Figure 1: case study design

Participants / Sample

Participants will be Learning & Development professionals working within an organisational context. They will be working within an organisation’s ‘Learning & Development’ (L&D) or ‘Organisational Development’ (OD) unit, typically in roles such as instructional designer, Learning & Development Consultant, L&D / OD Business Partner, trainer / facilitator, training manager or other learning specialist.

This research will adopt the non-probability sampling strategy used by LaLonde (2011), in his exploratory study on the role of Twitter in developing and maintaining connections in educators’ Personal Learning Networks (PLNs).

Sampling method

Non-probability, purposive sampling will be used to select relevant participants. Criterion that potential participants need to meet for this study:

- Currently working as a learning professional in an organisational context

- Actively engaged in self-directed learning goals related to their professional practice

- Contactable

- Committed to participating in a week long activity diarising their learning activity and follow-up interview/s

Participants may be selected from membership lists of professional networking groups for learning practitioners, or possibly from the L&D or OD department of a single organisation using the sampling criteria defined above. So that different perspectives can be considered, and cross-case comparisons made, learning professionals employed in different roles (e.g. instructional designer, training manager, eLearning developer, trainer / facilitator) and with different levels of usage / confidence in social networking technologies will be selected for each case study.

Sampling size

As with most qualitative research, data collection and analysis will occur progressively with no predefined sample size (Neuman, 2003). Rather, sampling and data collection will continue until ‘saturation point’ or no further new information is forthcoming (Tuckett, 2004; LaLonde, 2011). LaLonde (2011), studying a similar topic, found 7 participants to be sufficient. Since this study will go into more depth with each case, it is anticipated that 2 or 3 cases will likely be covered.

Strengths and weaknesses

Purposive sampling enables participants from different learning practitioner roles to be selected for the purposes of cross-case comparison. Whilst purposive sampling is appropriate for this type of exploratory research (Neuman, 2003), the sample will not represent the ‘typical’ learning professional, and the research cannot claim generalisability. It is also likely to suffer from non-response and self-selection bias – diarising learning activity for a week plus a participation in an interview requires substantial commitment, so it is likely those who participate will already be professionally engaged. There is also likely cultural bias in the sampling frame, towards English-speaking Australians highly literate with social networking technologies.

Data collection

Three types of qualitative data collection methods will be used:

- Survey – A short survey will capture demographic information from participants, such as gender, age range, ethnicity, education level, role / job title, location, organisation in which they work, and level of usage and confidence with social networking technologies. This will enable cross-case comparison. This survey should take no longer than 5 minutes to complete and may be done online via Survey Monkey.

- Diary log – participants will complete a structured diary for 1 week logging specific details of any instance where they interacted with someone in their Personal Learning Network (PLN) for purposes relating to their professional practice. People are often unconscious of their own learning processes in the workplace (Eraut 2004; Ellström 2011 cited by Rausch, 2013), including the contacts they connect with for learning (Rajagopal, Verjans, Sloep & Costa 2012). Diary methods collect self-report data closer to real time. This helps to overcome the bias of retrospective questionnaires or interviews commonly used in workplace learning research (Rausch, 2013) and social network analysis (Baker-Doyle, 2008; Feld & Carter, 2002), and captures data in a natural context, without the direct intrusion of the researcher. Aside from providing upfront guidance and instruction on the process of data collection, and check-ins to encourage consistent diarising, the researcher will be a ‘non-participant’ in the data collection.

Data will be collected by participants on interactions with their Personal Learning Network through the structured diary log. Each time they interact with a member of their PLN for purposes related to their professional practice they will record the following details:

- Who they interacted with

- How they interacted (e.g. the specific tool/technology used, face to face, phone etc)

- The purpose of the interaction

- Whether the connection was internal or external to the participant’s workplace

The diary may be modelled on Colbert’s (2000) ‘Rendevous Diary’ described by Lallemand (2012), a simple, and similar event-contingent diary suitable for this study. It may be created as an interactive Word or PDF form which participants may complete electronically or print.

- Semi-structured interview – follow up interview with participants via phone or Skype will be conducted (and recorded) about a week after the completion of the diary log. Interviews will be approximately 60 minutes. The purpose of these interviews is to clarify diary entries and further probe the nature of PLN relationships and interactions relating to improvements in their professional practice identified in the diary.

Questions in the SNA survey tool from Baker-Doyle’s (2008) case study of teacher networks will be used to identify relevant details about the nature and history of the learning professional’s relationship with key contacts. This will include: degree of closeness, frequency of interaction, and types of discussions typically conducted about their professional practice, regularity of these conversations, degree of influence the contact has had in inspiring changes to professional learning philosophy and practice, degree to which they share or offer advice to each contact.

Any diary interactions relating to improvements in professional practice will be probed to identify what changes were made as a result of the PLN interaction, and any challenges faced by the learning professional in implementing the changes.

An additional follow up interview may be employed to capture data on the evolution of changes made to professional practice (e.g. whether they were implemented and/or sustained).

The research site for the diary activity will occur in-situ – where-ever participants interact with their PLN. This may be at their workplace, home, or any other number of locations. The follow up interview will likely be via ‘Skype’ or telephone.

Ethical issues

This research will be conducted only with the informed consent of participants, and in compliance with National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. Approval will be obtained from the University of Sydney HREC body.

The small sample sizes increase the likelihood that participants may be identifiable. To mitigate this, pseudonyms will be used and the organisations participants work for will not be named.

Analysis

Manifest content analysis of diary log data will be conducted to identify any PLN interactions that may relate to improving the participant’s professional practice.

Participant validation of this analysis will be done through the follow up interview with participants. This participant verification of a researcher’s account is good practice (Eraut 2000), and contributes to reliability of data (Hotho et al. 2012). Following transcription of the interviews, manifest and latent coding of the transcripts will be conducted to identify themes relating to key concepts.

Responses on diary log and interviews will be cross checked, providing “checks and balances” for each data type (Baker-Doyle, 2008).

Cases will be compared for common themes or differences, narratives will be constructed for each case to create rich descriptions, with the aim of developing a grounded theory on the PLN interactions and relationships that contribute to improvements in professional practice.

Timetable

It is anticipated that collecting, transcribing and analysing data, and the writing of the final report will take about 9-12 months.

| December 2014 – January 2015 | Literature review |

| January, 2015 | Seek ethics approval |

| February – March 2015 | Case 1 data collection, transcription, analysis |

| April – May, 2015 | Case 2 data collection, transcription, analysis |

| June – July, 2015 | Case 3 data collection, transcription, analysis |

| August – October, 2015 | Writing up findings |

Dissemination

The results of the study will be disseminated to the participants. A thesis will be written up and offered for presentation at relevant conferences and/or submitted to journals such as Australian Vocational Education Review.

References

Baker-Doyle, K (2008) Circles of support: New urban teachers’ social support networks. University of Pennsylvania, ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing, 2008

Bell, R. L., Maeng, J. L. and Binns, I. C. (2013), Learning in context: Technology integration in a teacher preparation program informed by situated learning theory. J. Res. Sci. Teach., 50: 348–379.

Bessant, J; Alexander, A; Tsekouras, G; Rush, H and Lamming, R (2012) Developing innovation capability through learning networks. Journal of Economic Geography Volume 12, Issue 5 Pp. 1087-1112

Bonderup Dohn, N (2014) A practice-grounded approach to ‘engagement’ and ‘motivation’ in networked learning. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Networked Learning 2014, Edited by: Bayne S, Jones C, de Laat M, Ryberg T & Sinclair C.

Brown J.S and Duguid P (1991) Organizational Learning and Communities of Practice: Towards a Unified View of Working, Learning, and Innovation. Organization Science 1991 2(1): 40-57 http://people.ischool.berkeley.edu/~duguid/SLOFI/Organizational_Learning.htm

Burt, R.S (2000) Structural Holes versus Network Closure as Social Capital. Preprint for a chapter in Social Capital: Theory and Research. Edited by Nan Lin, Karen S. Cook, and R. S. Burt. Aldine de Gruyter, 2001. Retrieved from http://snap.stanford.edu/class/cs224w-readings/burt00capital.pdf

Dasgupta, M and Gupta, R.K (2009) Innovation in Organizations: A Review of the Role of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management. Global Business Review, 10:2, 203–224

de Laat, M and Schreurs, B (2013) Visualising informal professional development networks: building a case for learning analytics in the workplace. American Behavioral Scientist 57 (10) 1421 – 1428

De Laat, M; Lally, V; Lipponen, L Simons, RJ (2006) Analysing student engagement with learning and tutoring activities in networked learning communities: A multi-method approach. International Journal of Web Based Communities 2 (4), 394-412

Eraut (2000) Non-formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. British Journal of Educational Psychology 70, 113-136

Fleming, L; Mingo, S & Chen, D (2007) Collaborative brokerage, generative creativity, and creative success. Administrative Science Quarterly, September 2007 vol 52 (3), 443-475

Fridlund, B (1997) The case study as a research strategy. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences, 1997, Volume 11, Issue 1, pp. 3 – 4

Haythornthwaite, C & De Laat, M (2010) Social Networks and Learning Networks: Using social network perspectives to understand social learning. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Networked Learning 2010, Edited by: Dirckinck-Holmfeld L, Hodgson V, Jones C, de Laat M, McConnell D & Ryberg T

Hemphala, J and Magnusson, M (2012) Networks for Innovation – But What Networks and What Innovation? Creativity and Innovation Management Vol 21 (1) November 2013 http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/902/

Hotho, J. J., Becker-Ritterspach, F. and Saka-Helmhout, A. (2012), Enriching Absorptive Capacity through Social Interaction. British Journal of Management, 23: 383–401

Kijkuit, B and van den Ende, J (2007) The Organizational Life of an Idea: Integrating Social Network, Creativity and Decision-Making Perspectives. Journal of Management Studies 44 (6)

Lallemand, C. (2012). Dear Diary: Using Diaries to Study User Experience. User Experience Magazine, 11(3). Retrieved from http://uxpamagazine.org/dear-diary-using-diaries-to-study-user-experience/

LaLonde C (2011) The Twitter experience: the role of Twitter in the formation and maintenance of Personal Learning Networks. Retrieved from http://thesis.clintlalonde.net/

Mackey, J & Evans, T (2011) Interconnecting Networks of Practice for Professional Learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning Vol 23, no. 3http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/873/1682 retrieved 10th November 2013

Martin, J & Handcock, T (2014) New Roles Emerge for Learning and Development. TD Magazine http://www.astd.org/Publications/Magazines/TD/TD-Archive/2014/10/Webex-New-Roles-Emerge-for-Learning-and-Development

Neuman, W.L. (2003) Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Fifth edition, Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Obstfeld, D (2005) Social networks, the tertius iungens orientation, and involvement in innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly

Phelps, C; Heidl, R and Wadhwa, A (2012) Knowledge Networks: A Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Management, July 2012; vol. 38, 4: pp. 1115 – 1166

Rajagopal K., Joosten–ten Brinke D., Van Bruggen J., & Sloep P. (2012) Understanding personal learning networks: their structure, content and the networking skills needed to optimally use them. First Monday 17 (1-2) http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3559/3131

Rajagopal K, Verjans S, Sloep P.B, Costa C (2012) People in Personal Learning Networks: Analysing their Characteristics and Identifying Suitable Tools . Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Networked Learning 2012, Edited by: Hodgson V, Jones C, de Laat Retrieved from: http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fss/organisations/netlc/past/nlc2012/abstracts/pdf/rajagopal.pdf

Rausch, A (2013) Task Characteristics and Learning Potentials—Empirical Results of Three Diary Studies on Workplace Learning. Vocations and Learning (2013) 6:55–79

Ryberg, T & Larsen, M.C (2008) Networked identities: understanding relationships between strong and weak ties in networked environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 24, 103–115

Swan, J & Scarbrough, H (2005) The politics of networked innovation. Human Relations; Vol 58 (7), 913-943.

Tagliaventi, M.R; Mattarelli, E (2006). The role of networks of practice, value sharing, and operational proximity in knowledge flows between professional groups. Human Relations 9.3 (Mar 2006): 291-319.

Tuckett, A. (2004). Qualitative research sampling-the very real complexities. Nurse Researcher. 12(1): 47-61. Accessed 14 September 2012 http://digilib.library.uq.edu.au/eserv/UQ:114279/UQ_AV_114279.pdf

Van Den Hooff, B; Van Weenen, F; Soekijad, M; Huysman, M (2010) The value of online networks of practice: the role of embeddedness and media use. Journal of Information Technology, suppl. Special Issue on Social Networking 25.2 (Jun 2010): 205-215

Whelan, E (2007) ‘Exploring knowledge exchange in electronic networks of practice”, Journal of Information Technology’. Journal Of Information Technology, 22 :5-13

Whelan, E; Parise, S; de Valk, J; & Aalbers, R (2011) Creating employee networks that deliver open innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review 53 (1) 37-44 http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/creating-employee-networks-that-deliver-open-innovation

Add a comment