Reading Response: Chapter 8 – “Social learning and new literacies in formal education” / War of Art, Forward

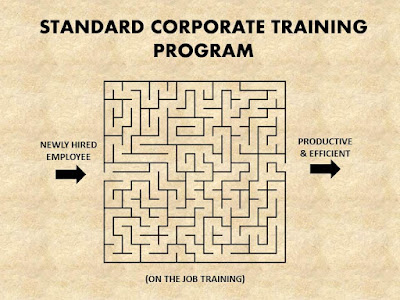

Firstly, to confirm mine and other classmates’ assessments of the “push” and “pull” models of instruction last week, Colin Lankshear and Michele Knoble write that some push is needed, saying “naturally, there has to be some ‘push’” (2011, p. 232). I agree that in most instances of instruction, there is some element of ‘push’ required. In high school there is a lot, as student are required to takes certain curriculum. In undergrad programs, students must complete certain courses listed in their “general education,” or, as in my case, their “liberal arts core.” Lankshear and Knoble write the some push is required in this Master’s program. My sister who is currently pursuing her doctorate says she is influenced by push as well. In my new job, I experienced some push during the onboarding process.

After reading Chapter 7, I think readers of Lankshear and Knoble want to vilify push because A.) it’s technique can be rather ineffective, and B.) we’ve all experienced forms of push, and it doesn’t feel very good! Nevertheless, I think if it is used in limited quantities, push can be helpful. It should be used as gentle guidance, rather than forcefully jamming facts, practices, philosophies, etc. into brains. Instruction should, as Lankshear and Knoble write, “try to promote as much immersion as possible in the logic of ‘pull’” (2011, p. 232). Unfortunately, trying to pursue pull in certain situations, like high school, may be met by barriers of standardization. Circumventing these barriers may require a lot of creativity on the part of teachers. (I am not a teacher, so I cannot precisely examine or critique how this could happen, but I am sure it could be a difficult process.)

Moving on, Chapter 8 really describes many of the strategies and outcomes of this summer’s Digital Storytelling course, especially in the way Lankshear and Knoble outline the the Master's coursework: “1. To address the theme of ‘new’ literacies… in theory and practice,” and “2.) To provide an introduction to literacy research” (2011, p. 233). Additionally, they write of Q2L that the learning was facilitated through “sharing, reflecting, responding to and providing feedback, evaluation, and distributing knowledge and understanding” (2011, p. 248).

Altogether, I think Lankshear and Knoble accurately describe what I think transpired in the Digital Storytelling class; students became “full participants in… social practice, acquiring deep kinds of learning… where participants learn to do and be in ways of competent insiders of practice” (2011, p. 252). We may not have become exactly “Digital Storytellers” – if there is such a Discourse – however, I think we learned deeply by “doing” new literacies in the form of telling stories digitally.

The final chapter was kind of funny to read, because my Week 6 reflection for this course described how ‘meta,’ or self-referential this course – and even this program – feels. This chapter really affirms that. At certain moments, I commonly murmured a popularized phrase, “Ah, I see what you did there.”

The War of Art, Forward

In an effort to follow this notion of being self-referential, I thought instead of trying to find another piece of text online about writer’s block, I would read the Forward to The War of Art by Robert McKee. In it, McKee describes his impression of Steven Pressfield and his book.

McKee summarizes each of the three parts to The War of Art, as well as his personal experiences with the book and other books that Pressfield has written (The Legend of Bagger Vance, Gates of Fire, Tides of War). Of the first part, my favorite part, he writes “Pressfield labels the enemy of creativity Resistance his all-encompassing term for what Freud called the Death Wish – the destructive force inside… that rises whenever we consider a though, long term course of action” (2003). He writes about how Part Two is about the “campaign of the professional,” and how Part Three informs us that inspiration is divine (though McKee disagrees, saying inspiration manifests through talent).

Reading the Forward prompted me to reflect on how The War of Art is constructed to influence the reader to pursue their creative goals, and how much of Pressfield’s advice about beating Resistance, and “turning pro,” is a form of “push” instruction. McKee writes that Pressfield demands “preparation, order, patience, endurance, acting in the face of fear and failure” (2003). This type of insight can be interpreted as the guidance creators need. However, the remaining methods that the reader can implement to achieve their creative goals follows more of a “pull” model.

It could be a stretch. At times, its been hard to relate New Literacies and The War of Art. Still, I wonder how self-help books, like The War of Art, could be interpreted in the forms of “push” vs. “pull” models of instruction. (Or even cook books!) They have a proclivity to stuff the mind with practices and philosophies, however, they are sought after, and can be open-ended.

Citations

Lankshear, C. & Knoble, M. (2011). New Literacies: Concepts and Theories. In New Literacies: Everyday Practices and Social Learning (3rd ed., p.232, 233, 248, 252). New York, New York: Open University Press.

Pressfield, S. (2003). The War of Art: Break through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles (Forward). New York, New York: Grand Central Publishing.