-

This is a test post to check my feed into DS106. In a way, it's kind of like sending a message to the future...

-

Where The Ocean Meets The Sky Meets The Land

Image Crop of Panoramic DS106 Surreal Panorama VisualAssignments, VisualAssignments1330

I have been fascinated with surrealism art since I first learned about it when I was in highschool (1998). I was captivated by the works of Rene Magritte and Salvador Dali among several other incredible surrealists. What is interesting about surreal art, is that it often times combines photorealistic qualities to give a sense of realism yet something isn’t quite right with the juxtaposition of the elements in the scene. The viewer gets an odd sense of an alternate reality or dream like state. The inspirational works of surrealism provides a creative lens to the tangible world, and the world of visual arts.

Rough Concept Sketch The works of Magritte has had such a profound impact on my interest in art, I chose to pay homage to the influence by focusing on the “water” and “clouds” in the scene I created. Many memorable works of Magritte include manipulation of clouds and water in juxtaposition with objects that are not naturally part of the environment. Initially, I drew a sketch of “sea clouds” with ships upside down and the earth landscape rendered as clouds.

However, after I starting creating I flipped the canvas and turned the boats right-side up. The decision to do this was because I did not feel the viewer could be as engaged without a natural gravitational sense. The viewer did not feel so inclined to look at the protagonist (the two boats in the foreground). The surprising result to doing this made the water look as though it was falling due to gravity and the “cloud earth” looks like a bubble or containment for the environment. Overall the experience of reliving my memories of Magritte’s work and creating the artwork itself was very satisfying.

The technical details to creating this work in Photoshop is fairly challenging. However, starting out with great images will simplify the process. Fortunately, I am familiar with a website frequented for video game designers who create level art called CGtextures.com. I’ve been using the website since 2006 for various video game projects. I downloaded several images of landscapes that I knew could work for the image I had in mind. I also perused my own photo library from a weekend vacation I took to San Diego, CA. I was able to get the water and the boat pictures from my own photo library. I began by stitching the landscape and clouds together to make a panoramic style image. From there I literally cut out cloud shapes with the selection tool over the images of water and pasted them into the scene. The most work involved creating the “sea clouds”. I used the warp tool and distort tool on my shapes and then used the smudge and erase tool on the edges of the shapes to get the feathered look. I used custom brushes that I created for past project painting backgrounds and clouds for games. I cut out the boats and changed the saturation and value on them to blend them into the scene. Finally, I flattened the image and applied some adjustment layers to increase the color and contrast.

Full Panoramic

Tips for success:- Create a sketch first.

- Find appropriate images to match the design in your sketch (use royalty free or personal photos).

- Keep it simple. Focus on foreground, middleground, and background development.

- Have fun experimenting!

Enjoy the DS106 easter egg! -

Day One: Try not to bleed out or faint.

Although technically day three of this class I debated for two days whether or not to drop this class. It is not because I don’t want to engage in a free thinking class but rather I am terrified of learning so much new technology in such a small amount of time. Coming from a person who… More Day One: Try not to bleed out or faint.

-

DS106 AB: Visual- Say It like the Peanut Butter

For this assignment from DS 106, it asked us to make a GIF from a movie of our choosing. With my interested in games I decided what better than a GIF from Wreck-It Ralph. I think this will be a great start in my focal work in Games and Diversity!

-

DS106 AB: Visual- Say It like the Peanut Butter

For this assignment from DS 106, it asked us to make a GIF from a movie of our choosing. With my interested in games I decided what better than a GIF from Wreck-It Ralph. I think this will be a great start in my focal work in Games and Diversity! -

The Daily Create-To My Parents

Dear Mom, I want to express how much you mean to me because I am not always able to. You and dad came here to America with hopes to make a better life for not only yourselves but also for your children. I want to express how proud I am to be your son. I understand that growing up you wanted to give me everything, through all the struggles you and dad have been through coming to America was one of the hardest things either of you had to do. To leave your family behind and to come to a country -

The Daily Create-To My Parents

Dear Mom, I want to express how much you mean to me because I am not always able to. You and dad came here to America with hopes to make a better life for not only yourselves but also for your children. I want to express how proud I am to be your son. I understand that growing up you wanted to give me everything, through all the struggles you and dad have been through coming to America was one of the hardest things either of you had to do. To leave your family behind and to come to a country -

DS106 AB: Visual- Say It like the Peanut Butter

For this assignment from DS 106, it asked us to make a GIF from a movie of our choosing. With my interested in games I decided what better than a GIF from Wreck-It Ralph. I think this will be a great start in my focal work in Games and Diversity! -

Above Treeline 2015-06-10 15:40:00

FALLING OUT OF LITERACY:A 21st Century ParadoxRemember when being literate was as simple as reading and writing? When you got "hooked on phonics" and demonstrating understanding only required a pen and paper? Or, better yet, remember when once you were... -

The Daily Create-To My Parents

Dear Mom, I want to express how much you mean to me because I am not always able to. You and dad came here to America with hopes to make a better life for not only yourselves but also for your children. I want to express how proud I am to be your son. I understand that growing up you wanted to give me everything, through all the struggles you and dad have been through coming to America was one of the hardest things either of you had to do. To leave your family behind and to come to a country you -

Sweet Message

Good Morning,Today my sweet message goes out to my mom living in Madrid, Spain. She is the strongest, most confident women I've ever met and has given me the strength to be the person I am today. Thanks mom! There are a million more t... -

The Beginning of Digital Storytelling

This blog is the starting shot of an 8 week sprint through the world of digital storytelling. Success, as stated by the course syllabus, will come through a careful understanding of four dispositions: course affinity with DS106, course location, social... -

Jason Dunbar 2015-06-10 00:08:17

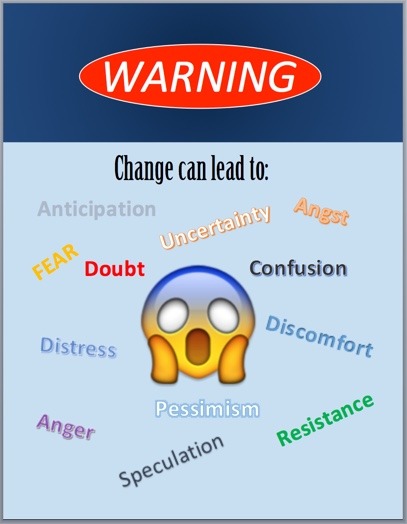

Warning of Change Everyone experiences change throughout their lifetime – new manager, birth of a child, loss of a pet, etc. I created this “warning” poster to illustrate some of the negative feelings and emotions we encounter during the initial phase of change. It’s important no to feel ashamed or embarrassed when we feel this… More

-

Warning of Change#visualassignments #visualassignments1549…

Warning of Change

#visualassignments #visualassignments1549 #ds106 #cudenver15

Everyone experiences change throughout their lifetime - new manager, birth of a child, loss of a pet, etc. I created this “warning” poster to illustrate some of the negative feelings and emotions we encounter during the initial phase of change. It’s important no to feel ashamed or embarrassed when we feel this way. These are all natural emotions to experience; however, we should work on finding constructive ways to channel these emotions, especially in the workplace, so we do not disrupt or damage the personal or professional relationships.

-

Who’s the best baby in the world?

Sir Oliver (Ollie) Dise is approximately 9 months old. He is just over 2 feet tall, slim build, with blonde hair, hazel eyes and has two bottom front teeth. This young man is wanted for being the best baby ever. The list of his crimes include: sleeping through the night at eight weeks old, always […] -

Rear-View Montage: Travels of my Past

I am a lot of things. I’m a sister, a daughter, a grad student, a Social Media Strategist, yada yada ya– the list goes on. But, most importantly, I like to think of myself as a photographer and a traveler. Both bring me great joy and pleasure and I couldn’t imagine my life without my camera and some kind of… Read more →

The post Rear-View Montage: Travels of my Past appeared first on Emily S. May.

-

Me in a Wordle

My life is full of adventure, there is never a dull moment, and I love every minute of it! Here is my life in a nutshell...(Word cloud created using Wordle for DS106 Visual Assignment) -

Heritage Conservation: Celebrating Culture and Designed Spaces Through Adaptive Reuse

#DS106 #VisualAssignments #VisualAssignments1701 When I saw this assignment in the DS106 bank, I immediately knew what photo I wanted to use. The challenge was to color change a photo, creating a new or different perspective on the environment. I lived in this building, the old Hot Springs High School, during the year I spent in Arkansas. President Bill Clinton attended high school here and graduated in the class of 1964. My studio loft was a largely unchanged classroom with massive windows -

The Daily Create//A Drawing Using Only One Shape

The circle has meaning across the many cultures of the world. For some, the circle represents wholeness, centering, and unity. Others see the circle as a symbol of revolution, nuturing, and cycles. Overall, the circle has a universal connotation of infinity and inclusion. In celebration of these themes, I chose to use the circle in my first ever The Daily Create through DS106. If you are unfamiliar with DS106, have a look at the open course on digital storytelling (more like a movement!) and -

The Daily Create//A Drawing Using Only One Shape

The circle has meaning across the many cultures of the world. For some, the circle represents wholeness, centering, and unity. Others see the circle as a symbol of revolution, nuturing, and cycles. Overall, the circle has a universal connotation of infinity and inclusion. In celebration of these themes, I chose to use the circle in my first ever The Daily Create through DS106. If you are unfamiliar with DS106, have a look at the open course on digital storytelling (more like a movement!) and -

Reading Response: Chapter 1 – “New Literacies: Concepts and Theories”

Reviewing the term “literacy” was an interesting study because I only knew it, as Colin Lankshear expressed, as a word that “came to apply to an ever increasing variety of practices” (2011, p. 12). I had no concept of the term’s history and evolution into becoming such a commonly used word to define a person’s proficiency or mastery of a practice. Nevertheless, Lankshear points out the criteria for literacy is deeper than proficiency, or mastery, or experience, et cetera-et cetera.

Early on, literacy was a term used to identify whether a person could read or write, and read or write well enough to perform proficiently enough in their daily work. While minoring in Economics as an undergrad, I learned that one of the criteria of a growing or high-performing nation was its literacy (the strongest performing countries having high rates among women). Lankshear notes that literacy is associated with “a country’s ‘readiness’ for ‘economic take-off’”(2011, p. 7). If you peruse through the CIA World Factbook (which I commonly used to analyze economic statistics and indicators), you can view country’s literacy rates – which the Worldbook defines as appropriate for people ages 15 and above who can read and write.

What was eye-opening to me, was the deeper notion of literacy explained in the “three dimensional model.” Beyond the operational dimension (the read/write proficiency of literacy), the meaning-making aspects of the cultrual dimension, and the value-defining elements of the critical dimension were new concepts to me, and made me wonder how these standards would apply to war traumatized countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, or Syria. What kind of literacy do these nations have under the three dimensional model? At what rate are people able to, as Lankshear wrote, “speak up, to negotiate and to be able to engage critically with the conditions of their working lives” (2011, p. 19).

Aside from the larger, global view of literacy, I wondered about my own literacties when Lankshear wrote about the multiplicity of literacy and how literacy now means “to ‘be on the inside’ of a form or field of knowledge” (2011, p. 21) and “being able to ‘speak’ its language” (2011, p. 21). In my own experience, as with many people, I’ve had to adjust to new literacties when changing jobs, or changing industries; even getting into new hobbies, such as sports, or music, come with their own literacies. Yet, when Lankshear wrote about digital literacies, I thought about my experience joining Twitter as an assignment in my Social Media and Digital Cultures course in the Spring 2014 semester. More broadly, I’ve adjusted to the many digital literacties since enrolling the University of Colorado Denver Learning Technologies Master’s program. I remember when joining the program I was more concerned about learning the ideas and concepts ` instructional design, or as Lankshear wrote “a critical, action-oriented ‘academic approach,’” (2011, p. 23) rather than learning how to build a e-learning module with Dreamweaver (the “skills based vocational approach” (Lankshear, 2011, p. 23)) as I thought these concepts would be more beneficial long-term because technology changes so rapidly, and I feared a more vocational education may become quickly irrelevant.

Lastly, there are two other concepts I felt were important to understanding digital literacy, or “new literacies.” As a proponent of Connectivism, I enjoy Lankshear’s idea of the ethos of the internet, and that new literacies are “more ‘participatory,’ more ‘collaborative,’ and more ‘distributed’” (2011, p. 29). However, when sharing or collaborating, people should also have what Howard Rheingold called “crap detection” (Lankshear p. 25.). Crap detection, or more eloquently called “critical consumption” is an ability to know what is “worth attending to in terms of quality, relevance, and the like” (Lankshear, 2011 p. 25). This notion of deeming what is relevant is also present in Connectivism: what is correct now, may be incorrect tomorrow because of shifting realities, and learners must comprehend these shifts when analyzing incoming information.

Chapter 1 of Lankshear’s New Literacies: Everyday Practices and Social Learning provides cultural context, definition, and critical analysis to the term “new literacies” before we dive further into the subject matter, which is a nice meta cognitive practice of providing literacy. Now I could say I am more "new literacies literate."

Citations

Lankshear, C. (2011). New Literacies: Concepts and Theories. In New Literacies: Everyday Practices and Social Learning (3rd ed., p. 7, 12, 19, 21, 23, 25, 29). New York, New York: Open University Press. -

Above Treeline 2015-06-09 10:40:00

CRUISING (TDC Shape Picture) This took a bit of time to figure out how to get the image from Adobe Draw on my ipad to flikr and beyond! At any rate, I don't draw but I thought I would step out of my comfort zone. Fun! -

Week One: The Daily Create 6/8/15

Hey everyone! Hope your summer is of to a great start! After a nice and rejuvenating break, I’m back at it– summer classes officially started yesterday. Before I jump into it, I’d like to mention that after my last post, I received an A in my Social Media and Digital Cultures class. YES! All the hard work did indeed pay… Read more →

The post Week One: The Daily Create 6/8/15 appeared first on Emily S. May.

-

DS106 – 1st post

Adding a post to this category, so that I can use it for DS106. -

-

“Digital Graffiti” – The Daily Create tdc1247

Today was an exciting day! Today I took my first steps into the world of DS106 with my digital storytelling class at UC Denver. I have been familiarizing myself with DS106 and Twitter over the past couple of weeks, and it is truly amazing, but I did not watch Jim Bloom's "Ed Parkour" lecture until today. Through this lecture I really learned what DS106 is about. It's about everything and anything interesting and creative. Free and open, sometimes with complete disregard for purpose, intent, or rules. Thus parkour... Some see pre-determined pedestrian pathways of concrete and metal, others see the greatest obstacle course ever made. Some see the web as a giant money-making corporate machine, other's see the greatest educational opportunity in the history of humankind. I can't wait to learn from my fellow classmates as well as the larger group of DS106 contributors around the world!To start things off, I dove right in and created something for the daily create. The limiting factor of the assignment was to use only one type of shape to create something. I chose circles and whilst exploring the circle concept I came up with this "digitized" circle image. Somewhat inspired by the concept of parkour - I put a graffiti spin on the assignment. Like parkour, graffiti art is another form of creative expression often times most successfully produced in urban sprawl. I call it “DS106 Digital Graffiti.”The Daily Create #dailycreate #DS106 -

Circles, circles and more circles!

Today’s daily create asked us to create an image using only one shape. I created this image out of circles. It’s a good representation of my life right now. Colorful organized mess! -

I really don’t know what I’m doing…

Do any of us really know what we’re doing in life? Life is one big learning adventure that we’re all on together! Especially being a new mother, I definitely don’t know what I’m doing! I’m always worrying about doing the right thing, and maybe I should be more concerned about just doing the best I […] -

Place holder for cudenver15 tag

This is just a test. -

Jason Dunbar 2015-06-08 17:36:33

“Sun Day” The Daily Create Assignment – Shape Picture I have never thought of myself as a creative/artistic individual. When I made a comment to one of my instructors that I didn’t have an artistic bone in my body, the instructor told me “if you have a soul, they you have creativity within you” (Thanks… More